Image at Left: "Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night" by Charles Burchfield is shown as part of the Burchfield Mural in downtown Salem, Ohio.

In July, during our visit to Youngstown, we spent an afternoon in nearby Salem so we could visit the Burchfield Homestead, a place that memorializes the life and art of the well-known water colorist Charles Burchfield. On the walls of Burchfield’s well-preserved childhood home hang prints of many of his works, especially those from his time in Ohio and from what’s known as his Golden Year of 1917 when he developed his mature style. Burchfield learned to depict the natural world in an intense and celebratory way and to show, both creatively and effectively, the harms human beings inflict on the land. But the image that held my attention that day was “Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night” because it was in the very house in which we stood that Burchfield had the experiences that led him to paint what is really more a portrait of a mood than of an actual place.

As I looked at “Church Bells Ringing” I couldn’t help but wonder: What is that shape hovering in the space between those two dark houses, slippery in the oily black rain? Does it have eyes and a beak? Does it have wings? And yet I already knew the answers to those questions, that the central image was in fact the spire of Salem's Baptist Church, since destroyed by fire, which when Burchfield was a boy tormented him with its tolling bell. It sounded to him like "a dull roar... dying slowly and with a growl.” He would listen to it on stormy winter nights, and it filled young Burchfield with a sense of dread. (1) The artist added another layer of personal meaning to this work that involved a visual language of Burchfield's own making, in which certain shapes and lines are part of what he called "Conventions for Abstract Thoughts." There were also "audio-cryptograms," which were meant to make visible certain sounds, like the ringing of a church bell. And so, unlike works such as “Coke Ovens at Night" in which Burchfield depicts harms done to the natural world, "Church Bells Ringing" contains no flames or clouds of smoke, no seared landscapes that would understandably create a sense of alarm. Just two houses, a church and a darkened sky, with the rain falling down. And yet how ominous.

If Burchfield were still alive, had he been around this

year when the Norfolk Southern train derailed in nearby East Palestine and sent flames and toxic

smoke into the air, he might very well have painted that scene, giving it

the sense of urgency and anxiety depicted in his other images of environmental devastation. After all, he worked in Wellsville and East Liverpool,

among other small Ohio towns, so why not East Palestine? But if he had gone back there

six months later, his response might have been different. He might have painted

something like “Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night” to show that though

the flames and clouds of smoke are long gone, there is still a lot of anxiety

and dread in that town, at least for some of its citizens. Only in this case, the sound he might have depicted with an audio-cryptogram would have been the long drawn-out wail of a train whistle.

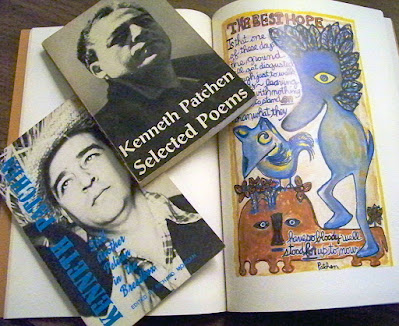

Earlier on the day on which we visited the Burchfield Homestead, we had seen a different image of “Church

Bells Ringing." It’s incorporated into the Charles

Burchfield Mural in downtown Salem, which commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Golden Year. Right across the street from that mural is LiBs Market, a café space and shop whose owner, Ben

Ratner, was an extra in the film version of White Noise, the Don DeLillo

novel in which an airborne toxic event ensues after a truck collides with a

train carrying toxic chemicals. When

we ordered our beverages, I asked at the counter if Ratner was around because I

wanted to talk with him about the film and the derailment, but I was told he

wasn’t there that day. Nonetheless, I knew, based on an interview he did with CNN,

that he's very concerned about the derailment. His house is a

mile from the crash site, he and his family were forced to evacuate, and he and his wife are worried

about their family's health, the future value of their home and their overall financial

security as a result of the derailment.

Knowing this increased the sense of dissonance I felt when,

during our visit to the Burchfield Homestead, we spoke with a local woman who

told us she didn’t really think there was anything to worry about in East Palestine. She implied that the response to the derailment was overblown, that

the creeks (i.e., Leslie Run and Sulphur Run) “had been polluted for a long

time,” and that people needed to return to normal. I thought about the things

Ratner had said, and I wondered how two people who lived so near to the site of

the derailment could feel could so differently about it. But the area near the derailment is

in fact a divided community in which some people feel that they aren’t getting

the assistance they deserve and continue to experience serious and worrying physical

symptoms while others just want to get back to normal.

July 14, 2023; photo by G.S. Evans

I had wanted to see for myself what East Palestine was like, and so we had made a short trip to the town a few days previously. We stopped the car on Taggart Street near the railroad tracks, and there was still a crew working on cleanup. We saw signs that said "Road Closed" and called for an identification badge check, but there were few other outward indications of what had happened there. We got out to take a few pictures, and in the one above you can see a dark van. On one side it said, "What's in your air?" and on the back was the notice: "Monitoring in progress." The unfamiliar sight of air monitoring trucks made me feel uneasy, and the fact that there were houses standing so near the place where flames had shot into the sky and a huge roiling cloud of black smoke had erupted gave me a feeling of deep empathy for anyone who had to stay there and still felt sick. I'm always the one who notices the chemicals, who gets a headache or a rash, and in fact after we had been there for a short time I felt nauseated and wanted to move on. Which of course the people who lived in those houses couldn't easily do...

On August 3, a few days after I returned to Arizona, I

attended the Virtual Symposium: East Palestine 6 Months After and got to hear

four community activists from the affected area talk about the derailment and its

aftermath. Each of them described her experiences of the event, as well as the

ongoing symptoms she and her family members continue to endure. They also

described feeling diminished by the EPA and other government agencies when told

there’s nothing wrong with the air and water in their communities. All four women have worked hard to

advocate for testing of air and water and have asked for monitoring of

people’s homes, but they all reported that not everyone in the community thinks there are

unresolved problems.

Hilary Flint, Vice President of East Palestine Unity

Council, said, "We're told that it's safe, and our pushback on that is

that safe is very subjective. It's not safe for everyone.” She said standards

being used to determine safety are based on OSHA data which usually involves

8-12 hour exposures on men and a single chemical, not multiple

chemicals. She added, “So when we're being told that it's safe -- a lot of

people, especially initially, believed that, and they said, ‘Oh, OK, it's safe. We'll go home.’ But what they didn't realize was that it wasn't safe for their

elderly family member. It wasn't safe for their child with asthma. It wasn't

safe for someone like me, a young adult cancer survivor with autoimmune issues.

We're told that it's safe, but they can't guarantee that for every single

person."

Asked to give advice to other communities faced with similar disasters, Amanda Kemmer, also of East Palestine Unity Council, said, "Right now the community is so divided between the people who say 'Everything is in your head,' versus those of us who are experiencing symptoms, and... they're really pushing hard with this PR narrative that everything is fine, everything is OK, and they're throwing a ton of money at this. Norfolk Southern is putting millions of dollars... to show that they're trying to 'make it right' but they're doing nothing to help the actual community."

Nearly two months later, on September 26, in a NewsNation Town Hall in East Palestine, Chris Cuomo focused extensively on the fact that many people continued to feel unwell. When he asked the roomful of attendees how many were still having symptoms, “experiencing things in a way that don't make sense to you physically and that they weren't like that before,” all but a very few raise their hands. Because Halloween is coming up, people in East Palestine were beginning to put up decorations, and Cuomo described the items that resident Shelby Walker had put up on her front lawn. The first is a scarecrow with the sign "Waiting for testing and the truth from Norfolk Southern... and the EPA," followed by a scarecrow with "Still waiting 5 months later," then a skeleton with "Still waiting 8 months later," and finally, tombstones with a sign that says "Too late..." "It's a macabre joke," Cuomo said, "but that's the mentality they have to learn to live with."

At the town hall they showed a short video of

Cuomo's visit to Walker's home, where she talked about the "sweet chemical

odor" that permeates her living space and said that one of

the derailed train cars was "right in my back yard." When Cuomo

asked her how she felt when officials and Norfolk Southern made the decision to do the controlled burn,

she said, "I just cried, because I thought... 'I may never have a home to

go home to.' Now today I wish that would have been the case. I wish my house

would have caught fire that day and I wish I would have lost everything."

She said she still has a mortgage to pay and asked who would buy her house now. She

said she is now on an inhaler, gasping for breath, and when Cuomo asked her if she and other disaffected residents are just looking for "a paycheck,"

she said, "Maybe some people are. Maybe they're not. Me, I'm not. I just

want to be safe. I want a home that's safe for my kids and my grandkids to be

at, and I want health insurance for them for the rest of their lives because we

don't know what's going to happen to us in five or ten years."

Of course, East Palestine isn't the only community where members have had divergent responses to an environmental disaster. According to sociology professor Becky Clausen, community response can vary, depending on the cause of the disaster. When it's an event that could be called a natural disaster, like a hurricane or flood, people tend to support one another and communities pull together. People consider the event to be an "act of God," with no one to blame, and in those cases support and resources often come quickly from outside sources. But in what she calls technological disasters, or "manmade" disasters, like toxic spills, communities become divided. Sociologists call this response the "corrosive community" because of the level of anger, stress, and loss of trust in institutions people experience, especially when support is slow in coming. These findings are based on sociological research on disasters like the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill in 1989.

Clausen advises people who live in a community where a technological disaster has taken place to "... understand that the reactions you may be experiencing (and those of your friends, family and neighbors) follow similar patterns of social/psychological stress... The confusion and uncertainty about the extent of health-related and economic impacts from environmental contamination create the psychological effect of 'invisible trauma.' Support is often needed to help people move through these reactions and to avoid further social and personal disruption." And yet, as the people quoted above indicate, support has not always been forthcoming in East Palestine, and the sense of corrosive community continues to deepen.

Clausen recommends setting up events at which people can help each other by listening to each other's stories, and the East Palestine Unity Council and other organizations have facilitated such events. She also recommends learning about similarly affected communities, and the people near the site of the derailment have benefitted from the wisdom of activists like Erin Brockovich and Marilyn Leistner, the last mayor of Times Beach. But when the EPA says the air and water contamination are "below action levels," people who don't have health symptoms may disregard the stories of those who do. And this is where things stand right now in East Palestine.

Adding to the confusion, the differences of opinion about East Palestine aren’t limited to the residents of Columbiana County and nearby Pennsylvania. There have been incidents of victim blaming in the national media, which contribute to the sense of corrosive community. (2) There have been white supremacist accusations that the government is purposefully trying to harm white conservatives in East Palestine. There have even been conspiracy theories making the rounds on TikTok.

Taken together, all of these things help to explain how people living in the same place at the same time can experience an event and its consequences so differently. But having heard so many residents of East Palestine say they don't feel safe in their own homes and knowing that, as Hilary Flint said, "safe is very subjective," I feel great empathy for those who want continued testing and monitoring. And having been in Charles Burchfield’s childhood home and seen his “Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night,” I think he might also have had great sympathy for those who don't feel safe in their own homes near the site of the derailment. Perhaps he would have found a way to depict the fear and anxiety that is provoked in the residents of a house standing near the tracks as they hear the insistent hooting of the horn of a train, barreling into town and bringing unknown dangers.

________________________________

(1) According to Nancy Weekly in her description of "Church Bells Ringing" for the exhibition, "A Dream World of Imagination: Charles E. Burchfield's Golden Year,” Burchfield himself noted the “[h]awk-like aspect” of the Baptist Church,” and he "animated the steeple to look like a ferocious bird.”

(2) Soon after the derailment, Briahna Joy Gray devoted a segment of her show, Rising, to what she described as victim blaming. She began by calling out Joy Behar, who in a February episode of The View "seemed to imply that East Palestine residents brought the disaster on themselves because they voted for Trump." She then showed a clip of Behar, who said, "[Trump] placed someone with deep ties to the chemical industry in charge of the EPA's chemical safety office," then pointed toward the viewers and added, "That's who you voted for in that district: Donald Trump, who reduces all safety…"

As a response to Joy Behar’s comment, Gray played another clip,

this time of former Ohio state senator Nina Turner making a more humane

assessment on CNN: “For the neoliberals who say that the residents of that area

deserve what they are getting, because they voted for President Donald J.

Trump, it is abhorrent. This is about poverty. It is about poor, working-class

white people who are enduring some of the same things that poor, working-class

black people endure whether it's in Flint, Cleveland or Jackson, Mississippi.

And so I want to lay it out. That the cultish behavior in politics right now

that it is a sin and a shame that when people are suffering to this magnitude

that you have people who will fix their mouths, to quote my grandmother, and

say that they are getting what they deserve. What they deserve is clean air, clean

food, and clean water, they deserve relief both in the short term and also in

the long term.”

Not only is Behar’s response not very humane, there’s also more

than a hint of schadenfreude about it. Such joy in the suffering of others,

especially if they are on the other side in our intensely polarized political

climate, seems to be on the rise in our country. A recent article in Scientific American cited a survey experiment in which over 35 percent of liberals agreed

with "the idea that those who do not believe in climate change 'get what

they deserve' when natural disasters strike them" and 36 percent of

conservative respondents expressed satisfaction "when those who support

restrictions on how businesses operate during the pandemic lose their job

because of government regulations." The authors of the article say, “Such 'joy in the suffering' of partisan others threatens to dramatically alter the

U.S. political landscape,” and it also threatens to make it difficult for

people to get the help they need when they are afflicted by an event, like the

East Palestine derailment, over which they had no control.