novelist. Photograph by Chester Kessler, circa 1952.

Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38096697

of the United States in Niles, Ohio. Photo by Lilly Conforti, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

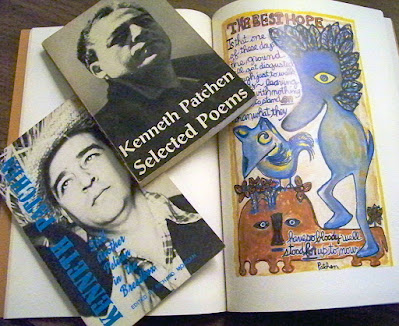

Two other creatures nearly fill the rest of the image, outlined against a yellow background and jockeying for space amidst the hand-lettered text of the poem, the last bit of which extends along the body of the standing ground. One of the creatures is a mix of animal, vegetable, and human, wearing leaves for hair and with a small tail, human-like legs and an elephantine sort of nose. It seems to be stepping down off the ground as it looks at us with one eye, the way someone does in an ancient Egyptian image, its head and body in profile and its eye gazing forward. The other creature is birdlike with swirling feathers and a pointed beaky face. It’s doing a good job of standing its ground and seems calmly balanced. Both creatures are yellow and blue.

But people are the subject of this Picture Poem, and none of these creatures are people. People are the ones who would be left with nothing more to stand on except for that which they have stood for, which sounds like an angry condemnation of people as a species, implying that they have stood for some terrible things. And, of course, they have. Yet when you look at the faces of all three creatures, you don’t really feel as though they or Patchen are angry at you. Instead, they seem to say that you had better be sure that you stand for something ethical and reasonable and well-thought-out, so you will have something to stand on under trying and difficult circumstances, which seems like sound advice to me.

For the second act of my small festival, I spent some time reading older poems from Patchen’s Selected

Poems, concentrating on the ones that have the most to do with Youngstown (when

it was a steel town) and on the air Patchen and I breathed there (though not

concurrently). “Orange Bears” (from Kenneth Patchen: Selected Poems) is one of the most anthologized of Patchen’s

poems and appears many places on the internet.

As the poet goes down by the “smelly crick” to read Whitman, he realizes that you have to have lived in a mill town to understand these injustices, because even Whitman, who was the quintessential poet of the American people, didn’t know much about “the National Guard coming over/ From Wheeling to stand in front of the millgates/ With drawn bayonets/ Jeering at the strikers…” And at the end the poem turns again to the air and the water and the land and tells us that “…you could put daisies/ On the windowsill at night and in/ The morning they’d be so covered with soot/ You couldn’t tell what they were anymore.” In this poem the industrialists who own the mills are shown to be just about everything the orange bears are not. Which is why the bears didn’t stand a chance where Patchen grew up in the 1920s and I grew up in the 1960s. Now the mills are gone and the jobs are gone and most of the most damaging effects on the river and the air are gone, but the sadness remains.

And though you might think

that “And May I Ask You a Question, Mr. Youngstown Sheet & Tube?” (also from Selected Poems) is going

to be an even more intense poem about those same issues, it is and it isn’t. It

does start out lamenting “…the yellow-brown smoke/ That blows in/ Every minute

of the day. And/ Every minute of the night,” but then there’s some dialogue between people who turn to alcohol in order to survive the exploitation and the gloom. And there’s less of a clear connection to issues of environmental justice and more

of a dramatic portrayal of how people try to keep themselves from despairing

when work is hard and unrelenting. At the poem’s end, in spite of death and

sadness and living with “the taste of tar in your mouth,” the poet announces that “[t]he day shift goes

on in four minutes.” In this way Patchen comments on the routinized and

standardized life of shifts and schedules that dominated people’s lives when

the mills were operating 24 hours a day. Now that they are not, people must

fend for themselves and the lack of the taste of tar isn’t always appreciated.

Finally, looking for a third act for my festival, I turned to Patchen as a playwright and listened to a 1942 radio play called “The City Wears a Slouch Hat,” which I found online quite by accident. It features a “sound score” by John Cage, which was commissioned by CBS’ Columbia Workshop to accompany a play written by Patchen. I was drawn to it because I encountered Cage’s avant-garde music the same year I first read Patchen, in 1970. Cage also directed the "orchestra of sound players,” consisting of five percussionists. There are gongs and chimes and bells and cymbals that fill in for the sounds of rain and ocean waves in the play, though sound effects are also used. In the play an unnamed man, referred to in the credits as "The Voice" wanders the cityscape on a rainy night, talking to people, generously giving a panhandler some money and listening patiently to a distraught woman. He also survives being mugged and harassed by street toughs, and he shows himself to have strange and more-than-human powers as, for example, when he goes up to answer a ringing phone on the sixth floor of a nearby building in order to tell the caller that a family will die in ten minutes time. We are given clearer evidence that he really has such abilities when we learn that he already has a picture of his mugger in his wallet and knows that the three men who later follow him have no bullets in their revolvers.

At one point he simply

says "Let's walk up and look around in the sky a bit." The percussion

score during that sequence is especially resonant, and it ends when he says,

"We better get back down, I guess." But The Voice isn't the only person

who has had unreal and unexpected experiences: one man tells another about a

talking horse, there's a machine that laughs and a woman who claims to have had

a terrible accident with broken glass that disfigured her, yet she is not

scarred and won’t explain. Toward the end of the play The Voice recites some

poetry ("The Passionate Shepherd to His Love" by Christopher Marlow

and "Death, be not proud" by John Donne), and then he swims out to a

rock in the ocean to get away from the city noise and strife, where he muses

that "I'll enjoy being alone..." But he soon encounters a man who says

he lives on that rock because he got "sort of tired of things onshore. Men

and women doing the same stupid things over and over. And the noise of the

city..." As he speaks, the sounds of percussion -- the gongs and chimes – substitute

for the frenzy of the waves.

After listening to what

the man on the rock has to say, The Voice turns his attention to the need for getting along with the other people around us and finding a way to accept the crowds

in the city. A slouch hat, which the city is said to wear according to the

play’s title, is mostly a military sort of headgear, and in the play the city is depicted as a place that can cause people to be defensive and fearful. But The

Voice cautions against this in his small final soliloquy, saying: "We were

not meant to be strangers to each other. We have the same fears, the same

hopes, joys, and sorrows. We must not be suspicious. We must learn to love each

other.” This might be a somewhat straightforward way to end such an avant-garde

play, but it’s a message that seems entirely appropriate coming from Kenneth

Patchen.

In this play, as in his

other work, Patchen advocates harmony and compassion. In his above-mentioned Christian

Science Monitor review, Steven Ratiner talks about the "powerful

pacifist message" of Patchen's art, and he notes that interest in Patchen's writing

was strong during the decade of the Vietnam war, which is when I discovered him.

Ratiner says that the poet’s work gained attention again in the 1980s

"when speculation about nuclear war and the survival of the planet [arose]

in daily conversation and newspaper headlines.” Since those speculations are

just as apropos today, I hope there will be a resurgence of interest in Kenneth Patchen's work, which also contained a great deal of wisdom about how human beings can

learn to live together without violence.

No comments:

Post a Comment