Anyone who has seen a haboob, which is the locally adopted Arabic word for dust storm, knows it is a much bigger and more challenging entity than a dust devil, yet it also seems to make the dust come to life. I walked through a mild haboob in downtown Tucson in May of 2012, but there are much larger dust storms that move ominously forward like a thundering herd of amorphous animals. Intense haboobs are more likely to occur along Interstate 10 between Phoenix and Tucson, but strong dust storms can invade the city as shown in the photo below.

Image of a haboob in Phoenix by Jasper Nance from Flickr.

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

I thought a lot about blowing dust and what the Dust Bowl must have been like for people in the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles when we traveled through that area last summer on our trip to Ohio. We stopped to see a little bit of the prairie land that is left in Missouri and Kansas, and we listened to excerpts of The Grapes of Wrath, but we weren't able to find a museum that focused on the experience of the Dust Bowl for the people who lived through it. After we got home, I read about the exhibit at the Chandler Museum called "Picturing Home: Dust Bowl Migrants in Chandler," but then, closer to home, I learned about the exhibit called “The Dirty Thirties: New Deal Photography Frames the Migrants' Stories,” which is permanently on display at the Tucson Desert Art Museum.

The “Dirty Thirties” exhibit is not made up of framed photos but of display panels that contain images and text relating to various aspects of the Dust Bowl. On the very first panel, the Arthur Rothstein photo from March of 1936 (see below) with the caption "Heavy black clouds of dust rising over the Texas Panhandle, Texas” sets the tone for the rest of the exhibit. This ominous and powerful photo shows massive dust clouds bearing down on a single car on a road still lit by the sun, though obviously it wouldn’t be for long. What makes the image especially effective is the brightness of the foreground and the darkness of the background, which give the viewer some idea of the sense of helplessness these rolling dust clouds would have elicited.

Rothstein, Arthur, "Heavy black clouds of dust rising over the Texas Panhandle, Texas," March 1936.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Courtesy of Library of Congress

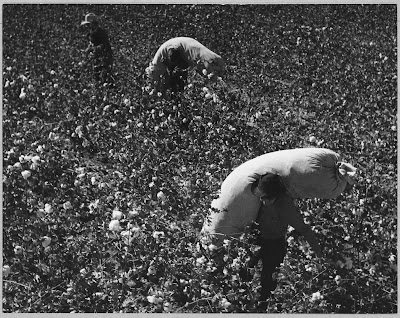

The exhibit, as the title suggests, is focused on photos by New Deal photographers, but I was especially interested in the section called “The Cotton Fields of Arizona” that features images by Dorothea Lange. In November of 1940 when many of these photos were taken, Arizona was an important part of the western cotton belt, and Lange recorded the experiences of migrant cotton pickers for the Farm Security Administration.

In New Deal Art in Arizona, Arizona State University Art History Professor Betsy Fahlman says that Lange’s Arizona photos are less well known than her other work, but they are “as compelling as any she took elsewhere.” (New Deal Art in Arizona, p. 94) Lange’s image (see below) of three workers, two of whom are weighed down and partly obscured by their bags of cotton, bears the caption "Cortaro Farms, Pinal County, Arizona. Cotton pickers with full sacks make their way through the field to the weighmaster at the cotton wagon." Because you can’t see the workers’ faces, they have a kind of anonymous quality that Fahlman says “…implies a depth of visual reference evoking a long art-historical tradition of picturing European peasants engaged in endless back-breaking labor, as defined by nineteenth-century French painters Jean-Francois Millet, Gustave Courbet, and others." (New Deal Art in Arizona, p. 99) And in fact the figures in the photo are similar in their postures and implied movements to the three women in The Gleaners, an 1857 painting by Jean-Francois Millet. More recently and closer to home, Peasants by Diego Rivera also suggests common work experiences by showing anonymous individuals.

Lange, Dorothea, "Cortaro Farms, Pinal County, Arizona. Cotton pickers with full sacks make their way through the field

to the weighmaster at the cotton wagon." November, 1940. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

to the weighmaster at the cotton wagon." November, 1940. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

These kinds of photos show Lange’s artistry off to good effect, but she is best known for her empathic portraits of individuals and families. Many such photos are included in “The Cotton Fields of Arizona” section of the exhibit, and they depict a surprisingly diverse group of cotton pickers, both male and female, who range in age from elders to young children, and include American Indians, African Americans, Mexicans and Mexican Americans, and whites who might be called Okies, Arkies, or Texies, depending on which Dust-Bowl-ravaged state they came from. In the image below, which is included in the exhibit, a man is shown wiping his mouth with the back of his hand, which half-covers his face and makes him seem wary and weary at the same time. The caption reads: “Near Coolidge, Arizona. Migratory cotton picker with his cotton sack slung over his shoulder rests at the scales before returning to work in the field.” The composition of this image is especially effective because of the prominence given to the palm of the man’s hand, the sharp angle formed by his bent arm and the wooden structure in the foreground, the toga-like folds of the bag over his shoulder, and the sense that he is restless though he is at rest. The photo elicits our sympathy, but it is only one of a huge number of images Lange took in the Arizona cotton fields. These photos show men and women pulling heavy bags of cotton, children struggling to pick from the prickly cotton plants, women caring for young children amid the squalor of the camps, and the range and variety of careworn faces of so many hard-working and worried people.

Lange, Dorothea, "Near Coolidge, Arizona. Migratory cotton picker with his cotton sack slung

over his shoulder rests at the scales before returning to work in the field." November 1940.

Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

over his shoulder rests at the scales before returning to work in the field." November 1940.

Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The text that accompanies the photos in the “Dirty Thirties” exhibit makes it clear that the events of the Depression were even harder for some people because of the racism that manifested itself in the way pickers were treated and even in the ways they were depicted. (Margaret Regan did a nice job of explaining this in her review of the exhibit in 2021: "Migrant Caravans: Photos from the New Deal Era Document Desperate Times." ) A documentary called “From Arizona's Dust Bowl: Lessons Lost,” which was produced by Arizona Public Media in 2012, examined these issues in great detail and featured a number of professors from the University of Arizona and other Arizona universities who answered questions about the Dust Bowl as it was experienced in Arizona.

One shocking example of racist treatment of workers was the so-called Repatriation of Mexicans – and even Mexican Americans who were citizens of the United States -- to Mexico. According to Professor of Agronomy, Agriculture and Life Sciences Jeffrey C. Silvertooth, between 1918 and 1920, 35,000 Mexicans were brought to Arizona to work in the cotton fields as Arizona’s cotton production expanded from 7,000 acres in 1916 to 180,000 acres in 1919. The low-paid labor of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans made it possible for the U.S. to make up for a shortfall of cotton imports experienced because of World War I. Then, according to History Professor Juan R. Garcia, Mexican workers were scapegoated and blamed for the economic troubles of the Depression, and many Americans became convinced that removing Mexicans would make things better. Anthropology Professor Thomas E. Sheridan said that during the Dust Bowl and Depression, the Federal government deported as many as 500,000 to 600,000 Mexicans and Mexican Americans, which in turn created a great demand for labor in the fields.

The Arizona Farm Bureau then advertised widely in Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, broadcasting the news that 5,000 families were wanted to work on 240,000 acres of cotton in the big cotton districts near Phoenix, Chandler, Casa Grande, and other places, including Eloy. The migrant Texies, Arkies, and Okies came, but they couldn’t earn anywhere near as much money as advertised. In New Deal Art in Arizona, Professor Fahlman says that “cotton growers optimistically reported that a good worker ‘could pick from 300 to 400 pounds of cotton a day, which would mean an income from $14 to $19 a week per picker.’ In practice, it was nearly impossible to earn these wages.” (New Deal Art in Arizona, p. 97) Migrant workers from Dust-Bowl-ravaged states experienced extreme hardship and terrible living conditions, and Professor Garcia said that the growers "replac[ed] one exploited group with another."

But what was it like to live in Arizona during the Dust Bowl? Despite the possibility of dust devils and haboobs, Arizona didn’t really experience the kind of blowing dust that made the Great Plains uninhabitable, and Arizona was less a victim of the Dust Bowl and more of a place migrant workers passed through on the way to California. One notable exception is the way dust in northern Arizona affected the lives of Navajo people. The documentary tells the heartbreaking story of how Navajo people were forced to slaughter their sheep and cattle because overgrazing was said to be creating soil erosion and the federal government feared that blowing dust would compromise the newly built Hoover Dam and silt up the Colorado River. "Stock reduction measures," according to Professor Manley A. Begay, currently in the Department of Applied Indigenous Studies at Northern Arizona University, created a "disastrous time in the history of Navajo people" because for them "livestock is life." "People were heartbroken by the sheer slaughter of thousands and thousands of animals," he said.

The Arizona Public Media documentary spends some time addressing the issue of blowing dust in Arizona, and I learned that our dust devils and haboobs form differently than Dust Bowl dust clouds and don’t last as long. Even so, according to Eric Betterton, Head of the Department of Atmospheric Sciences, if we want to mitigate dust, we need to try to control the sources, such as large areas of unvegetated or unpaved land.

Anyone who lives in southern Arizona has seen such areas of unvegetated and/or unpaved land and the resultant clouds of dust. I read about so-called "fugitive dust," and I was surprised to learn that even dust devils can be dangerous. According to the National Weather Service they can generate wind speeds of up to 80 m.p.h. and have caused property damage and injuries, largely because of blowing debris. Because of the small but real potential for harm, you should stay out of a dust devil’s way.

Dust devil in Arizona by NASA - NASA web page & source file, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5585657

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5585657

A haboob can be much more dangerous and can even cause serious health problems, since they carry particles of manure, pesticides, brake dust and tiny pieces of tires, along with Valley Fever spores. As I noted in an earlier blog post, according to an October 2020 article in Smithsonian Magazine, it is possible that the Great Plains could experience another Dust Bowl. Dust levels have been rising, as much as 5% per year, and the hotter, drier weather caused by climate change coincides with this trend, mimicking conditions that led to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. How that would affect Arizona is less certain, but we already have problems with dust mitigation here and certainly need to remain vigilant.